Brueggemann, Martin & Christian Doctrine

In 1986, aware that some within the Church were presenting an overly positive view of homosexuality, the CDF issued a letter to bishops on the pastoral care of homosexual persons. It made extremely clear what the Church has consistently taught on this issue and why:

"The issue of homosexuality and the moral evaluation of homosexual acts have increasingly become a matter of public debate, even in Catholic circles. Since this debate often advances arguments and makes assertions inconsistent with the teaching of the Catholic Church, it is quite rightly a cause for concern to all engaged in the pastoral ministry, and this Congregation has judged it to be of sufficiently grave and widespread importance to address to the Bishops of the Catholic Church this Letter on the Pastoral Care of Homosexual Persons.

2. Naturally, an exhaustive treatment of this complex issue cannot be attempted here, but we will focus our reflection within the distinctive context of the Catholic moral perspective. It is a perspective which finds support in the more secure findings of the natural sciences, which have their own legitimate and proper methodology and field of inquiry.

However, the Catholic moral viewpoint is founded on human reason illumined by faith and is consciously motivated by the desire to do the will of God our Father. The Church is thus in a position to learn from scientific discovery but also to transcend the horizons of science and to be confident that her more global vision does greater justice to the rich reality of the human person in his spiritual and physical dimensions, created by God and heir, by grace, to eternal life.

It is within this context, then, that it can be clearly seen that the phenomenon of homosexuality, complex as it is, and with its many consequences for society and ecclesial life, is a proper focus for the Church's pastoral care. It thus requires of her ministers attentive study, active concern and honest, theologically well-balanced counsel.

3. Explicit treatment of the problem was given in this Congregation's "Declaration on Certain Questions Concerning Sexual Ethics" of December 29, 1975. That document stressed the duty of trying to understand the homosexual condition and noted that culpability for homosexual acts should only be judged with prudence. At the same time the Congregation took note of the distinction commonly drawn between the homosexual condition or tendency and individual homosexual actions. These were described as deprived of their essential and indispensable finality, as being "intrinsically disordered", and able in no case to be approved of (cf. n. 8, $4).

In the discussion which followed the publication of the Declaration, however, an overly benign interpretation was given to the homosexual condition itself, some going so far as to call it neutral, or even good. Although the particular inclination of the homosexual person is not a sin, it is a more or less strong tendency ordered toward an intrinsic moral evil; and thus the inclination itself must be seen as an objective disorder.

Therefore special concern and pastoral attention should be directed toward those who have this condition, lest they be led to believe that the living out of this orientation in homosexual activity is a morally acceptable option. It is not."

Read the full letter on the Vatican website here.

Christians have always seen the family as the essential building block for society. Everyone is welcome -- Christianity does not discriminate, it is universal: It is grounded in the teaching that we are all made in the image and likeness of God. Sex is something extremely sacred; it is the way in which we share in creation, but it is dangerous. Misuse of our sexual appetite leads to abuse. Jesus teaches this Himself and is very passionate about it.

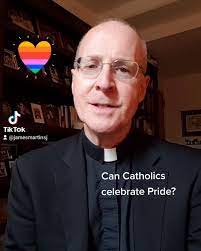

The Church should not have to constantly reiterate these fundamental basics. However, despite this clear instruction, the Church has continued to send mixed messages on this issue. The confusion has increased one hundred fold under Francis, Pope of Confusion. His endorsement of Jesuit Heresiarch Fr James Martin is a particularly pernicious. As is The openly pro-homosexual head of the European bishops’ commission who continually challenges the perennial Catholic doctrine on homosexuality and openly says he thinks the Catholic Church can change its teaching through the worldwide “Synod on Synodality,” a matter on which he assures us that he knows that he is “in full agreement with Pope Francis”.

A false division is often drawn up here between going out to call people to Christ: Christ who is the answer to the longing all human beings feel, and placing barriers which separate out the good from the bad. It is often considered that Pope Francis' reaching out to the marginalised is an imitation of Christ. I have discussed this here at length. Indeed it is, but there is a stark difference in that Jesus went out to the marginalised to call them to convert; to change their lives. Jesus is unequivocal in explaining who cannot achieve salvation (Mt 4:7 for example) and this clear instruction is echoed in the epistles of St. Paul (eg 1 Cor 6:9). Yes He does go out and rescue the one sheep, but He brings that sheep home, He doesn't leave it lost. This, surely, is the function and purpose of the kerygma, although we must be sure to build a bridge of love and trust before we help our brothers and sisters to properly hear the message.

Why, then, is Fr. James Martin citing a Protestant scholar and suggesting that he has figured out that why Christian tradition has been teaching error for over two thousand years?

Protestants argue biblical interpretations but Catholics rely on the Church to authentically interpret what Scripture means. On this basis alone Fr Martin is on extremely precarious ground, but let us look more closely at the argument here to see what we can make of it.

| Dr Ian Paul has a useful analysis of Brueggemann's essay here. I thought it would be valuable to use an evangelical Christian analysis to show how "one of the world's most renowned Biblical scholars" is attempting to justify something which is clearly unjustifiable from Scripture. Clearly. Crystal clearly!! Paul explains that Brueggemann makes some important and illuminating observations — you can read his essay here — but he also shows how Brueggemann smuggles in some massive assumptions about what the Bible is and what it isn’t, and all of these throw important light on the nature of the discussion about the Bible and sexuality. Dr Paul continues: "Perhaps the most interesting and significant thing that Brueggemann says, in the context of current discussions about the Bible and sexuality, come right at the beginning of his piece. He sets out by citing the ‘boo’ texts in Lev 18.22 and Lev 20.13, and adds to them Paul’s comments in Romans 1.23–27 (though, for some reason, he does not cite 1 Cor 6.9, which deploys a term that Paul coins from Lev 20.13). He then comments: "Paul’s intention here is not fully clear, but he wants to name the most extreme affront of the Gentiles before the creator God, and Paul takes disordered sexual relations as the ultimate affront. This indictment is not as clear as those in the tradition of Leviticus, but it does serve as an echo of those texts. It is impossible to explain away these texts."This is fascinating, and cuts right across much popular debate at the moment: ‘It is impossible to explain away these texts.’ Without feeling any need for explanation, he simply rejects attempts by popular writers like Matthew Vines, drawing on the largely discredited work of William Countryman and James Boswell, to claim that the ‘boo’ texts don’t really mean what they appear to mean. In taking them seriously and at face value, Brueggemann is agreeing with the vast majority of scholars on these texts." This approach does align with Fr James Martin's own approach which acknowledges that where Scripture speaks about homosexual behavior, it condemns it. Somewhat incredibly for a Catholic Priest in good standing, Martin openly questions whether the biblical judgement is correct. Brueggemann's argument is that despite the clear condemnation of homosexual acts in the Bible, taken as a whole, the Gospel message is one of welcome. The particular example Brueggemann uses here is the contrast between the regulation prohibiting the admission of the castrated to the assembly in Deut 23.1 and the inclusion of eunuchs in Is 56.3–4. He states: "This text issues a grand welcome to those who have been excluded, so that all are gathered in by this generous gathering God. The temple is for “all peoples,” not just the ones who have kept the purity codes."However, the text of Isaiah 56.4–6 states quite clearly: "To the eunuchs who keep my Sabbaths, who choose what pleases me and hold fast to my covenant—to them I will give within my temple and its walls a memorial and a name…"As Dr Paul points out, the welcome here is not to those who have failed to keep the purity codes, but an invitation to all to keep covenant obedience with God. And I am struck how this is ALWAYS the case, for example Luke 11:27-28 is exactly this. Brueggemann passes over the contrast between the prohibition on same-sex sex in Lev 18.22 and Lev 20.13, and the exclusion of the castrated in Deut 23.1: one is a prohibition of an act, the other is the exclusion of a kind of person. Isaiah appears to revise the latter but continue to affirm the former. And it is rather odd to take Matt 11.28 as a sign that Jesus makes no demands on his followers. The gospels are replete with comments from Jesus about how difficult and demanding it is to follow him. Our righteousness must exceed that of the Pharisees (Matt 5.20); if we are to enter the kingdom, we must travel on a hard and narrow way (Matt 7.14); for those attached to their wealth, entering the kingdom is impossible (Mark 10.27); indeed, all who follow Jesus must radically renounce their own interests, in principle their very life, in order to follow him day by day (Mark 8.34). We could go on! Brueggemann, reminiscent of Marcion, appears to claim an absolute contrast between the demands of Jesus and the demands of Torah: "Since Jesus mentions his “yoke,” he contrasts his simple requirements with the heavy demands that are imposed on the community by teachers of rigor. Jesus’ quarrel is not with the Torah, but with Torah interpretation that had become, in his time, excessively demanding and restrictive. The burden of discipleship to Jesus is easy, contrasted to the more rigorous teaching of some of his contemporaries. Indeed, they had made the Torah, in his time, exhausting, specializing in trivialities while disregarding the neighborly accents of justice, mercy and faithfulness (cf. Mt. 23:23)."Dr Paul comments: "I confess, as I continue to read the gospels, I cannot characterise demands of Jesus as ‘easy’! And Brueggemann seems to miss his own point: ‘Jesus’ quarrel is not with the Torah’. His first followers did not see the logic of his teaching as abandoning the need for obedience to Torah, and Jewish believers in Jesus continue in this approach today." Personally I recognise that Christian discipleship is challenging; part of the beginning of it is recognising we need help to be holy, but it seems to me the best way to live ones life. It makes marriage and parenthood a joy, it gives meaning and purpose and so you are happier, but properly happier not the kind of false joy that the world promises and never delivers. Brueggemann completes his focus on ‘texts of welcome’ with Peter’s declaration in response to his vision and encounter with Cornelius in Acts 10.34: "I truly understand that God shows no partiality, but in every nation anyone who fears him and does what is right is acceptable to him."Dr Paul notes that Brueggemann, focusing on God’s impartiality (which Dr Paul says is at the heart of the gospel), strangely ignores the requirement that we need to ‘do which is right’. Always and everywhere in Scripture, obedience is the essential response to grace. As always, the agenda trumps honesty. This then brings us to understanding Brueggemann’s assumptions about the nature of Scripture. He summarises the tension that he finds in Scripture in relation to ‘texts of rigor’ and ‘texts of welcome’ in this way: "I take the texts I have cited to be a fair representation of the very different voices that sound in Scripture. It is impossible to harmonize the mandates to exclusion in Leviticus 18:22, 20:13 and Deuteronomy 23:1 with the welcome stance of Isaiah 56, Matthew 11:28–30, Galatians 3:28 and Acts 10. Other texts might be cited as well, but these are typical and representative. As often happens in Scripture, we are left with texts in deep tension, if not in contradiction, with each other. The work of reading the Bible responsibly is the process of adjudicating these texts that will not be fit together."Dr Paul continues: "But, whilst he claims that it is diverse voices from different people in different contexts and places within the canon that are in contradiction, this is not the case. It is within the writings of single individuals that this tension appears—and Brueggemann is claiming that their own beliefs are in irresolvable contradiction, and that therefore, as a modern reader, he must adjudicate between the contradictory views of such people. It is the same Paul who wrote the text of ‘welcome’ in Gal 3.28 who also wrote the text of ‘rigor’ in 1 Cor 6.9, in which the term arsenokoites (otherwise unknown prior to Paul) is effectively a quotation of the Greek of Lev 20.13. The same Jesus who says ‘Come to me, all who are weary…’ also says ‘The road to life is hard and the gate is narrow, and those who find it are few’. And this continues to the final words of Scripture: the words of radically inclusive invitation in Rev 22.17 (‘Let anyone who is thirsty come and drink…’) follow on immediately from words of radical exclusion in Rev 22.15 (‘Outside are the dogs and the sexually immoral…’). His approach is summarised in his closing paragraphs, when he contrasts the gospel with the Bible: ‘The Gospel is not to be confused with or identified with the Bible.’ This is an approach that has been around for a long time, and was first practiced by German critical scholarship under the title Sachkritik, meaning ‘substance criticism’, the ‘substance’ meaning the assumed heart of the gospel message. (For an account of this approach over the last 100 years, see Robert Morgan’s article in JSNT here.) The various biblical texts are not all consistently faithful to the ‘gospel’ of the good news that God has for humanity; our task, therefore, is to discern what that ‘gospel’ is, drawing it out from the right biblical texts, and then using this to critique, and quite possibly disagree with and dismiss, contrary biblical texts. This is the approach that Douglas Campbell takes with the texts on sexuality in Paul: "If Paul was inconsistent at this point, as seems likely, failing to prosecute his soteriology with complete ethical consistency (and who of us can cast the first stone here?!), then I suggest that, having detected this, we should simply overrule those inconsistencies in the name of his central convictions. Paul’s soteriological centre, along with its consistent ethical corollaries, should trump his inconsistent ethical admonitions; his position on redemption should overrule his inconsistent statements about creation…[T]he result of this decision is that we should jettison Paul’s commitment to a binary, and essentially Hellenistic, theology of creation" (The Quest For Paul’s Gospel, p 127). We need to recognise here the assumptions that are being made in the use of this Sachkritik approach:

It is not possible to balance Brueggemann's equation it seems to me. In order to do so, one would have to believe that Jesus' mission was in vain, He failed to communicate the Good News effectively to humanity and that all we are left with is our own reasoning...In which case, if Christianity has had it wrong for two thousand years and secular society has worked it out better and faster, what's the point of biblical scholarship or even the Bible??? Dr Paul continues: "In the second half of his article, Brueggemann makes important observations about the task of biblical interpretation, in particular on the need for awareness by interpreters, and the importance of context. Every interpretation is indeed undertaken from a particular context, and we cannot ignore this. But Brueggemann appears to think that it is impossible to escape our context—which in turn means that his own view is possibly nothing more than a projection of his own concerns [my emphasis]. He does not countenance the possibility that any interpreter might allow Scripture to challenge and reform their own assumptions. [which surely is the very purpose of Scripture?]. We indeed cannot interpret without taking into account questions of context. That is vital, one of what I would identify as four essentials in reading scripture well. But the idea that our understanding of sexuality in the modern world is without precedent flies in the face of the evidence (that settled same-sex attraction and faithful same sex relationships were known in the ancient world) and against the claim of queer theorists that there have always been gay people in society. And there is no denying that different biblical texts, on first reading, appear to be in tension with one another on key issues of violence, slavery, the role of women—and, of course, Torah obedience. The question is: what is the nature of this tension? Is it to do with different cultural and contextual issues, or do these tensions arise from irreconcilable contradiction? In each of these contested issues, different texts at first appear to be in tension with one another as they refer to the subject directly. We do not have to reach for unrelated texts in order to counter the overall picture that Scripture offers. But here is the irony: whilst Brueggemann claims that ‘the Bible does not speak with a single voice on any topic’, the subject of same-sex sexual activity is the one issue on which the Bible does indeed appear to ‘speak with a single voice’ [my emphais]. Humanity is created male and female, in the image of God, and sexual union between a man and a woman is depicted as a reflection of that creation pattern. The Levitical rejection of same-sex sexual activity appears to be drawing on that account, and both Paul and Jesus refer to it explicitly, Jesus in his understanding of marriage, and Paul specifically in his rejection of same-sex sex, citing creation in Romans 1, and the Levitical code in 1 Cor 6.9 and 1 Tim 1.9. [For a beautiful and thorough exegesis of Jesus teaching on sexuality, which directly speaks to these issues watch this Youtube video]. So perhaps the most helpful thing that Brueggemann does for us in his article is to highlight that the debate about sexuality in the church today is, at heart, a debate about Scripture. Can we trust Scripture to speak the truth of God to us? Is Scripture ‘God’s word written’ which has a essential theological coherence (Article XX in the XXXIX Articles of Religion), or is it an amalgam of God’s good news to us mixed with sinful, even repugnant, human ideas, so that we need to select the one from the other, rescuing gospel gold from biblical dross? As Wolfhart Pannenberg has commented: "Here lies the boundary of a Christian church that knows itself to be bound by the authority of Scripture. Those who urge the church to change the norm of its teaching on this matter must know that they are promoting schism. If a church were to let itself be pushed to the point where it ceased to treat homosexual activity as a departure from the biblical norm, and recognized homosexual unions as a personal partnership of love equivalent to marriage, such a church would stand no longer on biblical ground but against the unequivocal witness of Scripture. A church that took this step would cease to be the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic church." |

We do indeed need to hold up a big sign of ‘Welcome!’ to all, regardless of sex, race, sexuality or situation. But it is a Welcome to follow the demanding path of life to which Jesus calls us [my emphasis]."

I'm grateful you've done the work of sifting Breuggemann and his lackeys through Paul-- I no longer have the patience for it (not that I ever did, not all that much, anyway). Thanks!

ReplyDelete